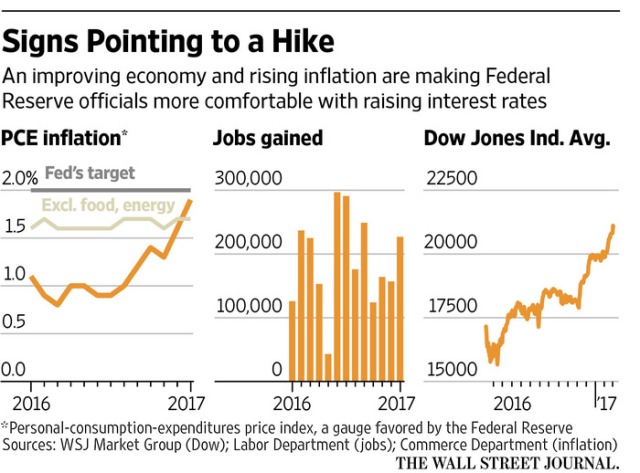

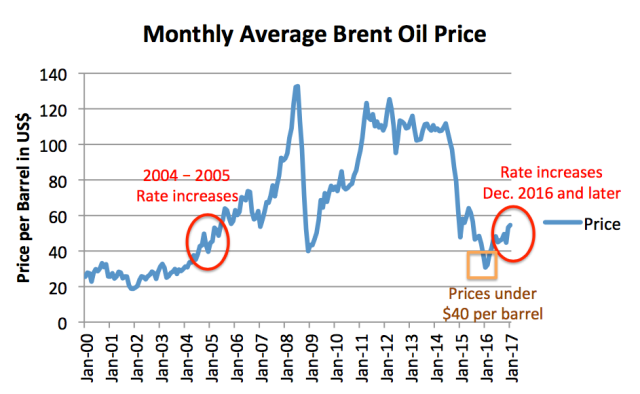

The Federal Reserve would like to raise target interest rates because of inflation concerns and concern that asset bubbles are forming. Part of the concern seems to be rising oil prices, compared to their low level in early 2016.

A finite world does not behave the way most modelers expect. Interest rates that worked perfectly well in the past, don’t necessarily work well now. Oil prices that worked perfectly well in the past don’t necessarily work well now. It seems to me that raising interest rates at this time is very ill advised. These are a few of the issues I see:

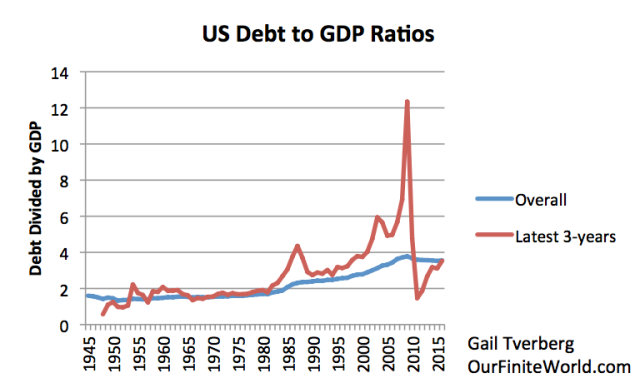

[1] The economy is now incredibly dependent upon rising debt to prop up its spending. The pattern of total debt to GDP for the United States is shown in Figure 2.

There was a huge increase in debt in the period leading up to the 2008 crash. Every year between 2001 and 2008, the increase in debt was greater than four times the increase in GDP. In fact, for some years in that period, more than $8 of debt were added for every dollar of GDP added.

We now seem to be starting a new run up in debt. In 2015, the amount of debt added was $2.5 trillion ($66.1 trillion minus $63.6 trillion), while the amount of GDP added was only $529 million. This indicates a ratio of over 4.7 for the single year of 2016. (Figure 2 shows only three-year averages, because of the volatility of amounts.)

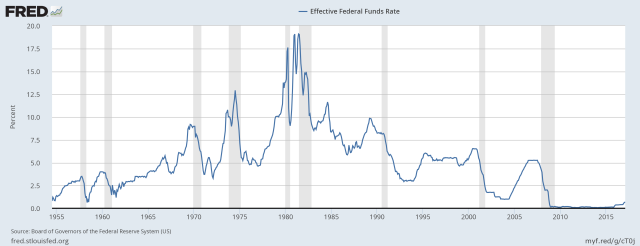

[2] The vast majority of the debt run-up since 1981 (Figure 2) seems to have been enabled by falling interest rates (Figure 3). Given how dependent we are now on large increases in debt to produce GDP, it would seem to be dangerous for the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates.

With falling interest rates, monthly payments can be lower, even if prices of homes and cars rise. Thus, more people can afford homes and cars, and factories are less expensive to build. The whole economy is boosted by increased “demand” (really increased affordability) for high-priced goods, thanks to the lower monthly payments.

Asset prices, such as home prices and farm prices, can rise because the reduced interest rate for debt makes them more affordable to more buyers. Assets that people already own tend to inflate, making them feel richer. In fact, owners of assets such as homes can borrow part of the increased equity, giving them more spendable income for other things. In fact, this is part of what happened leading up to the financial crash of 2008.

The interest rates that the Federal Reserve plans to change are of a different type, called “Effective Federal Funds Rate.” These also hit a peak about 1981.

[3] The last time Federal Funds target interest rate was raised, the situation ended very badly.

Figure 4 (above) shows that the last time Federal Reserve target interest rates were raised was in the 2004-2005 period. This was another time when the Federal Reserve was concerned about the run-up in food and energy prices, as I mention in my paper Oil Supply Limits and the Continuing Financial Crisis. The higher target interest rates were somewhat slow acting, but they eventually played a role in bursting the debt bubble that had been built up. In 2008, the amount of outstanding mortgage debt and consumer credit started falling, and oil prices fell dramatically.

It is ironic that the US government is again trying to bring down food and energy prices, when they are at a price level similar to the price level when they tried this approach the last time.

The Federal Reserve inadvertently seems to be comparing current oil prices to those in the January to March 2016 period, when they were under $40 per barrel. Using this comparison, rising oil prices appear to be contributing to an undesirably high inflation rate. Most people who have been following what is happening in the oil industry know that prices are not high, relative to the prices needed for profitability. Even if some US companies claim to be profitable at $50 per barrel, it is clear that, in general, the industry cannot withstand prices as low as they are today. At the current price level, investment is too low.

Part of the problem is that oil exporters need higher prices if they are to obtain adequate tax revenue to fund their programs. For example, Saudi Arabia has found that because of its falling tax revenue, it needs to borrow money to maintain its programs. This is a big change from being able to set aside money in a reserve fund, out of excess tax revenue. This is another place where the shift is toward more debt.

[4] The pattern the Federal Reserve seems to want to follow is the 1981 model, in which temporary high interest rates seemed to force energy prices down for a long time.

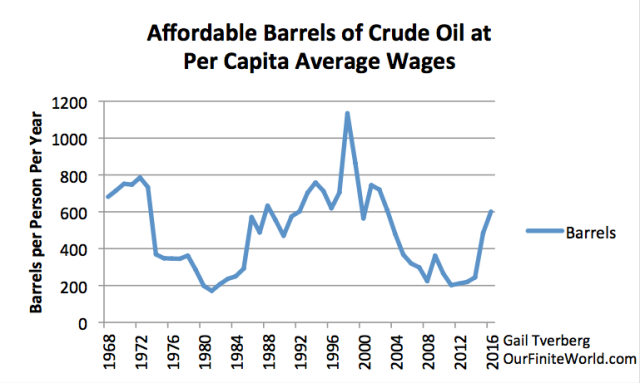

If we look at oil prices compared to US wages per capita (dividing total wages by total population), we find that oil “affordability” was at a low point in 1981. We saw previously in Figures 3 and 4 that interest rates were raised to a very high level at that time. The gray stripes in Figures 3 and 4 indicate that a recession followed.

Figure 6 shows that after interest rates fell, affordability rose until 1998. To a significant extent this was the result of falling prices, but it also was the result of a larger share of the population working, and thus contributing to rising wages.

There were many things that allowed this benevolent outcome to happen. One was the fact that we already knew about available oil in the North Sea, Mexico, and Alaska. When this oil came on line, oil prices were able to drop back to a much more affordable level. It is very doubtful that shale oil could play a similar role today, especially if it is likely that higher interest rates will drop oil prices from today’s $50 per barrel level.